By Isabelle Peeters – Underwater Gardens International

In the clear waters off southwest Tenerife, a quiet but powerful restoration effort is underway. At the heart of this initiative lies the sponge Aplysina aerophoba, whose vibrant yellow tubes do not go unnoticed, but whose ecological importance is profound. As part of the OCEAN CITIZEN project, this sponge is one of the selected species to be transplanted onto the artificial reefs that will be installed near Punta Blanca. But why Aplysina aerophoba? Because it’s not just a sponge; it’s a forest builder, a water purifier, a chemical powerhouse, and a cornerstone of biodiversity.

Aplysina aerophoba is a sponge found throughout the Mediterranean and eastern Atlantic, including the Canary Islands. It thrives in shallow, sunlit rocky habitats up to 25 meters deep in the Canaries. Its name “aerophoba” means “fear of air,” a reference to its dramatic color change from bright yellow to blue when exposed to oxygen. This sponge forms colonies of tubular structures that can reach up to 10 centimeters long, often aggregating into dense clusters. These aggregations are more than aesthetic, they are ecological infrastructure.

Sponges like Aplysina aerophoba are increasingly recognized as architects of “marine animal forests” (MAF) – complex, three-dimensional habitats formed by sessile organisms. In that sense, the tubular structures of A. aerophoba provide shelter and substrate for a wide range of marine life, including crustaceans, mollusks, juvenile fish, and algae. These sponge-dominated areas support high species richness and serve as nurseries for commercially important fish, while also stabilizing sediment and reducing erosion in dynamic coastal zones. In short, Aplysina aerophoba among other MAF species is a builder of underwater cities, quietly shaping the architecture of life beneath the waves.

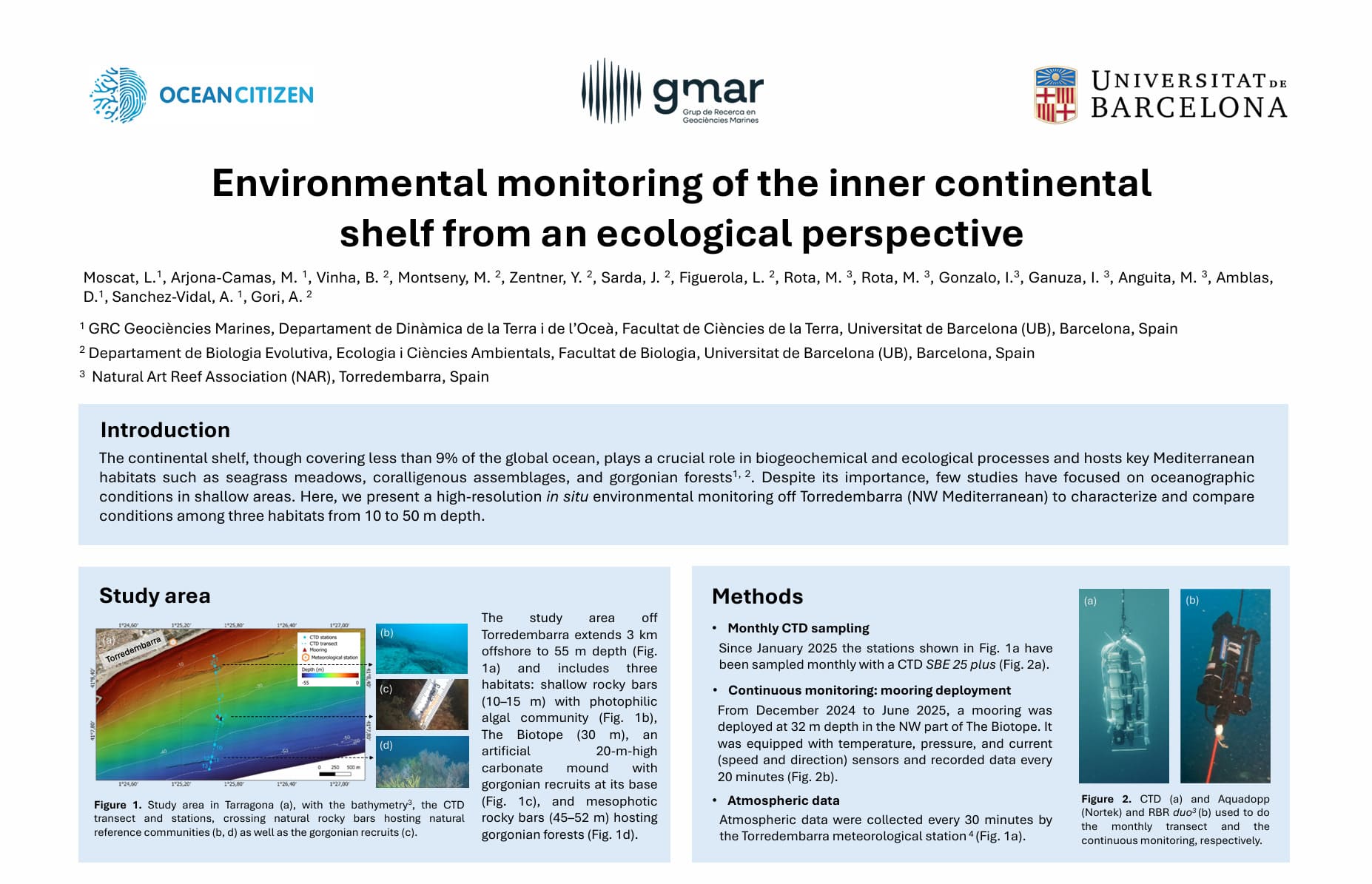

Aplysina aerophoba tubular marine forest (left) and close up of the sponge’s tubes (right).

Pictures: Isabelle Peeters

One of the most impressive features of A. aerophoba is its filtration capacity. Like other sponges, it draws seawater through its porous body, trapping bacteria, plankton, and organic particles. This process not only nourishes the sponge but also improves water quality, making it a natural ally in combating pollution and eutrophication. Research has shown that A. aerophoba is one of the most efficient biological filters in the ocean, capable of purifying vast volumes of water and enhancing the health of surrounding ecosystems.

Inside its tissues, the yellow tube sponge hosts a diverse microbiome that contributes to nutrient cycling and chemical defense. It produces brominated alkaloids which deter predators and inhibit microbial growth. These compounds are mobilized to the sponge’s surface when grazed or wounded, showcasing a sophisticated defense strategy. Despite this heavy chemical defense, A. aerophoba is grazed by the sea slug Tylodina perversa, which even adopts its yellow coloration thus displaying a rare example of chemical camouflage in the marine world.

Close up of Tylodina perversa grazing on A. aerophoba (left), and T. perversa on algae bed (right).

Pictures: Isabelle Peeters

Despite its powerful features, Aplysina aerophoba faces several threats. Climate change, with its rising sea temperatures and ocean acidification, can disrupt sponge physiology and microbial symbiosis. Pollution from heavy metals, plastics, and chemical runoff can impair sponge health and reproduction. Habitat loss due to coastal development and destructive fishing practices reduces available substrate and fragments sponge populations.

Currently, Aplysina aerophoba is not listed as endangered, but its ecological role makes it a priority for conservation. In the Canary Islands, it is considered common, yet localized declines have been observed in areas with high human impact. OCEAN CITIZEN’s transplantation initiative is a proactive step toward safeguarding this species. By introducing A. aerophoba to artificial reefs, the project aims to rebuild sponge-dominated habitats, enhance biodiversity, and monitor sponge health and adaptation over time. These efforts align with broader goals of developping scalable blueprints for marine restoration and climate adaptation based on MAF recovery.