Brown canopy-forming seaweeds are structural foundation species that can create extensive seaweed forests (Figure 1) considered among Earth’s most productive and biodiversity-rich ecosystems (Wernberg & Filbee-Dexter, 2019). These ecosystems offer invaluable ecosystem services, creating biodiversity hotspots supporting fisheries and enhancing ecosystem resilience against environmental fluctuations (Eger et al, 2023). Seaweed forests also participate in nutrient cycling and CO2 accumulation with an annual economic value of 500 billion US$ (Eger et al, 2023).

However, despite their importance in socio-ecosystem structure and functioning, seaweed forests are increasingly threatened and in regression worldwide (United Nations Environment Programme, 2023). This has resulted in the degradation of over 60% of marine forests worldwide in the last 50 years and total disappearance in some areas (United Nations Environment Programme, 2023). This, unfortunately, is happening also in Tenerife (Martín García et al, 2022), one of the OCEAN CITIZEN pilot sites. Several local and global stressors are involved in the regression of marine forests such as habitat destruction, pollution and invasive species spread, with climate change and especially ocean warming merging as an increasingly challenging threat (Smale, 2020).

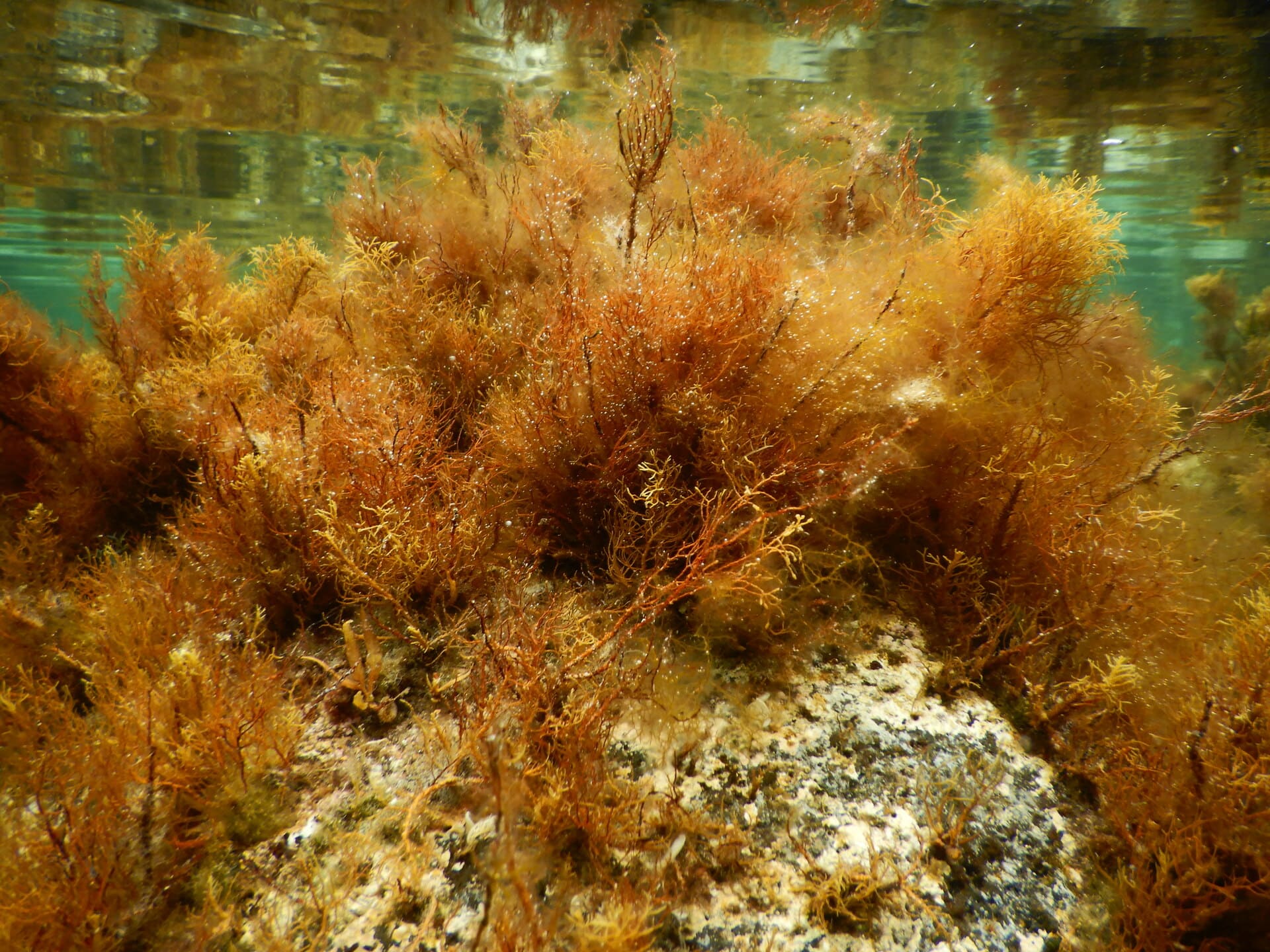

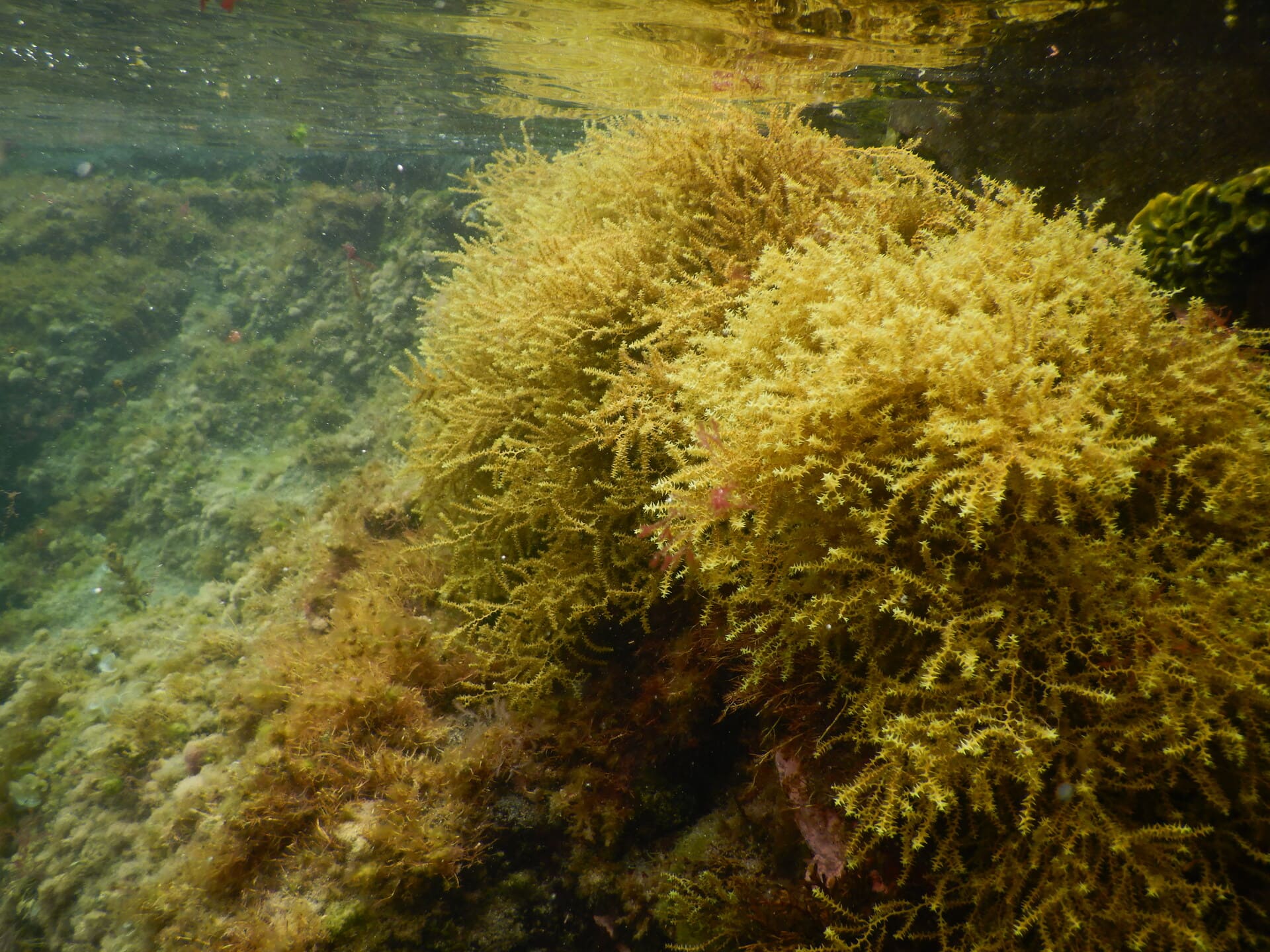

In Tenerife, seaweed forests are represented mainly by Cystoseira sensu lato species of the genera Cystoseira, Gongolaria and Ericaria (Molinari – Novoa & Guiry, 2020) (Figure 2) most of which are protected (Verlaque et al, 2019). These species dominate intertidal and sublittoral rocky bottoms and have functional traits similar to larger kelps (Wernberg & Filbee-Dexter, 2019). In the Canary Islands declines of 90% of the extension of some Cystoseira s.l. species have been reported in the last decades, mainly due to ocean warming and habitat degradation (Valdazo et al, 2017, 2024; Martín-García, 2021). These declines call for urgent actions to prevent further losses and restore areas unable to recover naturally: and here OCEAN CITIZEN is taking action!

Several preparatory steps are undertaken by the CoNISMa team to enhance the efficiency of future seaweed forests restoration actions in Tenerife. First, they are characterising the seaweed communities at the restoration site, establishing a critical baseline for evaluating restoration success and community evolution. They are also assessing habitat suitability after identifying potential stressors and evaluating potential donor sites for implementing ex-situ out-planting restoration techniques (De La Fuente et al, 2019; Falace et al, 2018). The ex-situ out-planting technique, which is a non-destructive restoration method, mandatory when working with endangered and protected species, consists of the obtention of seaweed seedlings on substrates for their later out-planting in selected restoration sites. The first step of this restoration technique is the collection of apical fertile branches of the considered Cystoseira s.l. species. The apical fertile branches, c.a. 4 cm long, are collected from a healthy donor population, this does not impact the population as Cystoseira s.l. species grow new branches annually. The apical fertile branches, containing mature receptacles are transported to the laboratory and subjected to a thermal shock by maintaining them at 4ºC overnight to stimulate the release of the gametes. After the thermal shock, the branches are placed on top of tailor-made clay substrates to release the zygotes on the substrates in the aquaria (Figure 3). After 24h the fertile branches are removed from the aquaria and the zygotes settled on the substrates will grow in controlled conditions for a few weeks until they are out-planted in the field in the restoration site (Figure 3). Finally, CoNISMa team is also developing a long-term monitoring protocol to assess the evolution and sustainability of the seaweed restoration and assess natural capital generation.

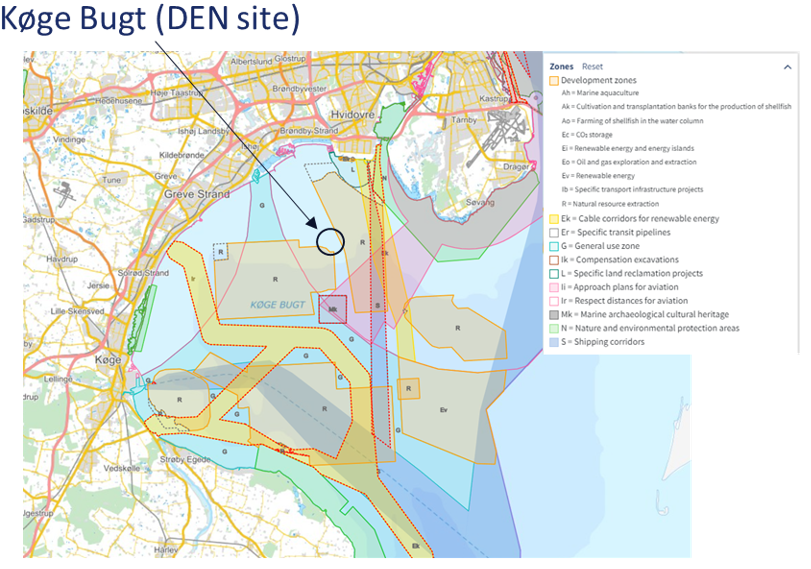

Three campaigns have been performed so far to better understand the seaweed diversity, define species of interest for restoration actions implementation, identification of healthy populations that can serve as donor sites and assess habitat suitability for a global restoration strategy (Figure 4).

Overall, this research will provide crucial knowledge for restoring marine biodiversity and sustaining the ecosystem services provided by seaweed forests.

The conservation and restoration of marine forests will ensure the long-term viability of the myriad benefits these ecosystems offer to marine life and coastal communities.

Authors: CoNISMa team

Bibliography

De La Fuente G, Chiantore M, Asnaghi V, Kaleb S & Falace A (2019) First ex situ outplanting of the habitat-forming seaweed Cystoseira amentacea var. stricta from a restoration perspective. PeerJ 7: e7290

Eger AM, Marzinelli EM, Beas-Luna R, Blain CO, Blamey LK, Byrnes JEK, Carnell PE, Choi CG, Hessing-Lewis M, Kim KY, et al (2023) The value of ecosystem services in global marine kelp forests. Nat Commun 14: 1894

Falace A, Kaleb S, Fuente GDL, Asnaghi V & Chiantore M (2018) Ex situ cultivation protocol for Cystoseira amentacea var. stricta (Fucales, Phaeophyceae) from a restoration perspective. PLOS ONE 13: e0193011

Martín García L, Rancel-Rodríguez NM, Sangil C, Reyes J, Benito B, Orellana S & Sansón M (2022) Environmental and human factors drive the subtropical marine forests of Gongolaria abies-marina to extinction. Marine Environmental Research 181: 105759

Martín-García L (2021) Decline of sublittoral canopoies from the subtropical Atlantic Ocean. The case of Gongolaria abies-marina (SG Gmelin) Kuntze 1891 in Canary Islands (Spain). Centro Oceanográfico de Canarias

Molinari – Novoa EA & Guiry E (2020) Reinstatement of the genera Gongolaria Boehmer and Ericaria Stackhouse (Sargassaceae, Phaeophyceae). Notulae Algarum: 1–10

Smale DA (2020) Impacts of ocean warming on kelp forest ecosystems. New Phytol 225: 1447–1454

United Nations Environment Programme NBFN (2023) Into the Blue: Securing a Sustainable Future for Kelp Forests.

Valdazo J, Coca J, Haroun R, Bergasa O, Viera-Rodríguez MA & Tuya F (2024) Local and global stressors as major drivers of the drastic regression of brown macroalgae forests in an oceanic island. Reg Environ Change 24: 65

Valdazo J, Viera-Rodríguez MA, Espino F, Haroun R & Tuya F (2017) Massive decline of Cystoseira abies-marina forests in Gran Canaria Island (Canary Islands, eastern Atlantic). Scientia Marina 81: 499–507

Verlaque M, Boudouresque C-F & Perret-Boudouresque M (2019) Mediterranean seaweeds listed as threatened under the Barcelona Convention: A critical analysis. 33: 179–214

Wernberg T & Filbee-Dexter K (2019) Missing the marine forest for the trees. Marine Ecology Progress Series 612: 209–215